|

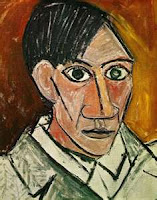

| Pablo Picasso Self-Portrait |

So much so, George unyieldingly went on, that according to some Spanish ideal he was almost obsessed by his own eyes; eyes that may even be seen as coming out of his paintings, time and a gain, staring aggressively at the beholder; eyes with which the artist is supposed to have claimed he was capable of seducing any woman he wanted, although he'd always been terrified by the possibility of contracting a venereal disease. Syphilis was rife in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries and couldn't be cured yet. But eventually that couldn't completely deter Picasso from entertaining various relationships.

George vehemently despised both the man and his paintings. The man, based on photos showing him as a young man during his days at Montmartre, Paris, because he considered him to overestimate himself to the point of insanity; and his paintings, mere rubbish to George, for the over-hyped oversimplification that only in the eyes of art critics could ever stand for something bigger just for the purpose of allowing those critics to justify their own professional existence.

|

| Pablo Picasso Self-Portrait |

Picasso's works, lauded by some art critics as bringing man, humanity and nature in a supposedly genial way down to two-dimensional basics, for George were mere degrading simplifications of reality, or perceptions of it, primitive and crude ones at that, that could be produced in almost no time at all, and then left to the critics and self-proclaimed art lovers to be interpreted and over-interpreted, and interpreted to bits until they were made to stand out and convince museums and art fanatics with too much money on their hands and who would regularly gravitate to Christie's or Sotheby's and other auction houses.

Picasso, in fact, had never said much about his paintings. A fact that could be seen - or interpreted - as proving George's point - perhaps, but not incontestably so. Compared to real works of art, he maintained, that on top of being breathtaking and impressive (not referring to any particular style, but I knew that George had always admired the works of Salvador Dalí), Picasso's paintings were mere amateurish cartoons that could easily be improved by a host of professional cartoonists who could technically outperform Picasso with ease.

|

| Weeping Woman by Pablo Picasso |

It was just a matter of time until this happened to buyers of Picasso's paintings, George claimed, and in a way he wasn't very wrong about investments of this kind in a more general sense, in particular when a painting turns out to be a fake or is claimed by a previous owner from whom it had once been stolen. Things like that have really happened but so far it hasn't to my knowledge occurred to a piece of art having lost substantially in monetary value, either gradually or in a sudden crash-like manner.

Therefore, George added, he wouldn't mind if all those investing in Picassos, for the sake of seeing them grow in value like precious metal or shares, ended up like investors in Dutch tulip bulbs that after the bubble had burst were left with nothing more than obscenely and impoverishingly expensive onions.

Though bored by stamp collections, George said that stamps might in the end be even more useful than Picasso's paintings. I was wondering if that also applied to stamps featuring Picassos on them, of which I'm sure there are some, and be that in Spain.

|

| Pablo Picasso Les Demoiselles d'Avignon |

I couldn't come to Picasso's rescue. Like George, I'd always admired Dalí, and both the man and his works are so strikingly different from Picasso and his works. In my admiration, I'm talking about Dalí's works of art, not about the artist personally.

I don't mean to say I was against Dalí's appearance in public in any way; I found him droll somehow, and at times I found him a little lost and at a disadvantage at an English-language talk show. Was he arrogant and pompous? Or did he disguise an ego problem? Did he even have an ego problem or was his ego simply big and boisterous to begin with? I'm not sure, and it doesn't matter much to me.

And would I want to defend Picasso at all? I could, instead, even deny having ever heard of the man the way he is said to have done with regard to African art that had influenced some of his works, including the Demoiselles, so distinctly, though his reaction was reported to have been "African art? What's that?"

One way or another, Picasso was certainly more than a simple two-dimensional scribbler. Looking at what he produced over many decades, one cannot help seeing him as a noteworthy multi-layered artist.

No comments:

Post a Comment